|

Inside the Box: The computer comes out to play

There's often a vertical plane between musician and audience. The sheet-music stand paved the way for the upturned plastic shell of the turntable, and today, chances are that rectangle obscuring the face of the performer on stage is the screen of a laptop computer, which has emerged as a ubiquitous music-making tool.

The laptop, however, obscures more than just the musician's face. Its uses vary too widely for it to be easily characterized. For some, the laptop is essentially a more portable equivalent of the DJ's turntables, mixer, and crate of records. But for many, it is a means to bring the power of computer processing into live performance, creating music of the moment that's comprised of all manner of sonic detritus: field recordings, sine waves, sound bites of pre-existing music, pure feedback.

Computer music is nothing new, though it has certainly blossomed in the past decade thanks to the rapid spread of personal computing. The question is: What's "laptop music"? How does the fact that the technology now is portable alter computer-enabled music? More than anything, the laptop has brought computer music not only out of the closet, but out of the house. And thanks to the laptop's compact size and ease of use, it's triggered several successive waves of adopters. "Laptop music," as a result, isn't really a genre, and since the laptop can run such a variety of music software, it may be inappropriate to simply call it an instrument. What is it? A phenomenon.

The laptop is a proverbial black box—well, generally speaking, a silver one, usually in this context affixed with a glowing Apple logo—and it has many inputs and outputs. The same could be said of its history and its future. This overview of so-called "laptop music" is an attempt to see what led up to this moment, to highlight some leading figures, and to look ahead to what "mobile music" might constitute down the pike. The laptop's a bit like an SUV. It's expensive and powerful and nice to look at, but how many people actually take it over really rigorous terrain? Well, plenty, in fact, from the microsonics of Tetsu Inoue, to the augmented field recordings of Christian Fennesz, to the spatial immersions of Carl Stone, to the fractured dance music of Autechre, all of whom have made the laptop computer one of their primary tools.

|

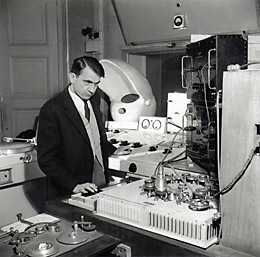

I initially studied computer science in college, and before I opted for an English degree, my favorite professor was an esteemed figure in the field by the name of Alan J. Perlis, a man who won the very first Turing Award (often described as the Nobel Prize of computing) the year I was born. He would often digress from a sequence of code that he was reciting from memory in order to tell us stories about the dawn of the study of computing. From today's standpoint, in a time of iPods and Tablet PCs, my own college education feels like it occurred during the Stone Age, with those monochrome monitors and rudimentary programming languages. But for Perlis, our cathode-ray computer-lab terminals and the Macintoshes popping up in dormitories were generations removed from his Cretaceous-era schooling.

Prof. Perlis appreciated our difficulty with the problems he assigned each week, those all-nighters we spent eradicating bugs. He told us that when he was a graduate student there was a commonplace way that programmers went about wrestling with a faulty bit of programming: You'd open up the computer you were working on, enter it, sit on a cozy chair and contemplate the machine from the inside. That image has never faded from my memory. If anything, it's become more vivid as computers have gotten smaller. This primer covering the laptop and its role in music today is a peek under the hood, now that the machines have gotten too compact to be entered directly.

***

Fast Backward: A brief prehistory of laptop music

In our everyday lives, phones double as cameras, high-tech supertitles accompany the opera, and TiVo automates the recording of PBS's latest adaptation of Charles Dickens' Bleak House. Alvin Toffler's pessimistic "future shock" is experienced primarily in hindsight, when we consider how quickly our lives have been altered; by and large, it's more along the lines of "past shock," when we recoil at the idea of life without high-speed Internet access, ATMs, and Netflix. And after momentary consideration, we shrug it off, flip open the latest Best Buy circular and further consume our way into a technologically mediated future.

We could credit ourselves as a species with high points for adaptability, but to do so would be to underestimate how well we've been prepared for these seemingly bold technological leaps—often by cultural trends and scientific discoveries that date back not just decades but hundreds of years. Modern robotics had its precursors in the Renaissance doodles of Leonardo Da Vinci, and the modern computer in the decidedly pre-industrial writings of Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace.

Likewise, the laptop music that even today might strike us as utterly new has certain precedents. These precedents prepared our imaginations, even if the technology that allowed the imaginings to be realized was a long time coming. There are numerous cultural currents that brought us to where we are now, but the following are six key 20th-century phenomena that prepared us for the 21st century: musique concrète, serialism, analog synthesizers, and hip-hop, along with the broader matters of the "studio as instrument" and rapid advances in computing.

|

Before there was sampling, there was musique concrète, a.k.a. tape and razor blades. Its origination attributed to Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) in the late 1940s, and its development to Pierre Henry (1927-) and John Cage (1912-1992), among others, musique concrète took recorded sound as the start, rather than the end, of the compositional process. Tape was cut and spliced, working with pure sound (a bird call, an overheard conversation, an orchestral performance) as an element of construction. Today, Xacto blades are used mostly for opening eBay packages, and audiotape has gone the way of photo-sensitive film, but the spirit of musique concrète lives on in the computer's agility with sampling and with molding whole segments of sound.

It would be quite understandable that one might glance at this year's classical concert offerings and imagine that serialism, and by extension twelve-tone music, had come and gone. But even more than musique concrète, serialism foresaw the computer's ability to perform functions on set blocks of prerecorded sound. Musique concrète may have introduced the idea that sound can itself be subjected to compositional play. However, it was serialism that posited the "row," or a fixed set of notes, as a sonic object, and thus composition as a paper algorithm that is enacted on that subset. Today's computer music, especially the live improvisation performed on laptops, enacts those transformations on sheer sound in much the same way. In place of "rows" we have "samples," and in place of the codified twelve-tone transpositions we have the endless variety of computer mediation, like granular synthesis, in which processing is applied to extremely narrow slivers of sound; surround-sound effects, in which sound can be moved around in three-dimensional space; and backward-masking, that hallmark of tape-editing, just to name a few.

|

We can now perform high-grade digital synthesis on the same machines we use to balance our checking accounts, but the origins of these so-called "soft synths" were the hulking analog synthesizers pioneered by the likes of Leon Theremin (1896-1993) and, later, Robert Moog (1934-2005) and tweaked to the point of ridicule by prog groups such as Yes. The histrionics of those rock performances may have earned some of the resulting backlash, but the globe-trotting bands served the purpose of road-testing the hardware. Even at this stage in the laptop's ascendance, several well-respected electronic-based musicians, such as Thomas Dimuzio, eschew the laptop due to its lack of dependability. It's also worth noting that the album Analord, the most recent release by Richard D. James, the electronic musician best known by the pseudonyms Aphex Twin and AFX, was performed entirely on vintage analog equipment—and as if to emphasize the old-school implication, the material was released initially as a series of vinyl 12"s.

The classical music world has, of late, wrestled with bringing hip-hop into the symphony hall. Witness Daniel Bernard Roumain's A Civil Rights Reader, which adds a turntablist to a string quartet, and the Asian Dub Foundation's commission by the English National Orchestra for an opera about Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

|

But hip-hop's influence on today's art music is far more elemental than those events suggest. Hip-hop was birthed on the cheap. Its legacy isn't merely a matter of having brought beats to the forefront of Western music; its legacy, at a more basic level, has to do with making the most of available technology, and with manipulating pre-existing sound in real time. Every time musicians pump a laptop's sound card into an amplifier, they celebrate the Bronx DJs who made history with two turntables and a microphone.

Those four, fairly self-contained phenomena occurred in the shadow of a broader sequence of events. Like many a revolution, the concept of the "recording studio as instrument" started with a counter-cultural bang and ended up on retail shelves. The Platonic ideal of using the recording studio to capture otherwise un-performable music dates back, in the public consciousness, to the separate but related decisions by the Beatles and pianist Glenn Gould to cease touring in favor of the studio's seemingly endless possibilities. Certainly there were precedents for "impossible" music—in, among other distinct realms, the tape constructions of Schaeffer and the player-piano machinations of Conlon Nancarrow. But there's no overstating the impact of a good spokesperson, and in the Beatles and Gould, not to mention the Beach Boys and other aural seekers of the 1960s, the recording studio had many prominent individuals in its corner. The creative use of the recording studio to construct unreal, or "hyperreal," music continued to evolve through producer Teo Macero's work with Miles Davis, Steely Dan's meticulously constructed pop, Brian Eno's development of ambient and, inevitably and somewhat pathetically, the rise of celebrities who must lip sync their "live" concerts, so unequipped are they to approximate their fetishistically manicured hit singles.

Dovetailing with the steady rise of the studio-as-instrument was a second revolution: the asymptotic advance of the personal computer, and its eventual impact on audio recording. During the past half decade, many professional studios have been shuttered as the computer became the de facto recording studio, trading tape for hard drives and replacing, or augmenting, mixing boards with software like Pro Tools. Portable computers continue to lag behind the desktops for processing power, due to the twin issues of miniaturization and cost, but not long after the Apple PowerBook appeared, along with the equivalent Microsoft- and Linux-based machines, a laptop was capable of producing sounds that could not just entertain a live audience but could capture a musician's imagination, even if it could not yet serve as a pro-grade console.

All of which has brought us to the present, to a moment when in music, as in life, computer literacy is increasingly essential to daily activity. What's important to recognize is that for all our easy adoption of technology, there's a strong tendency to doubt its efficacy, even its appropriateness, in the realm of art. Today, the computer plays a core role for most composers, whether they actively push the envelope with digital synthesis or simply use a software package such as Sibelius or Finale for notation purposes. Whether a composer treats the computer as an appliance or as an instrument is the lingering question.

|

I attended a lecture recently by musician Joshua Kit Clayton, who is also one of the programmers of the popular Max/MSP software. Max/MSP is a key application on many musicians' laptops; it's a language of sorts that allows users to code subroutines that can be applied to sound (and visuals, and more) or to other subroutines. Clayton was addressing an audience of undergrads at a prominent art school in San Francisco. The computer screen projected behind him was a Matrix-like spew, a flow chart of only somewhat comprehensible commands, boxes, arrows, and squiggly lines. It made the new math seem old hat by comparison. Perhaps sensing trepidation among his paint-stained listeners, he paused his geekily charismatic presentation to decry math illiteracy among musicians in particular and artists in general. Clayton sternly lectured the young audience: "Go home, smoke some weed, and get over your obstacles!"

***

Tool or Toolbox: The laptop's ever-changing role

|

When the Kronos Quartet performed in April 2006 at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, three laptops were in full view—four if you count the guy in front of me who kept pulling out his ultra-portable OQO device, a fully functioning Windows machine smaller than the average paperback. But let's stick to the concert. One of the laptops belonged to Walter Kitundu, who performed with the quartet at the end of the first set. The second laptop belonged to Drew Daniel, half of the electronic duo Matmos, which joined Kronos for the close of the second set. The third laptop belonged to Kronos sound designer Scott Fraser (an experimental musician in his own right), who sat behind a vast soundboard toward the middle of the hall and routinely checked the computer as the evening progressed.

All three laptops in the Kronos show were Apples. The Apple logo is as ubiquitous in electronic music as the Adidas logo once was in hip-hop, so this is no coincidence, despite Apple's slim market share. That glowing logo, however, is probably all that the three machines had in common. Even if they were running the same software, which is unlikely, they were being used for entirely different purposes, yet all in the service of Kronos' performance. Daniel's was most certainly the source of the pumping rhythms that grounded Matmos's collaboration with Kronos, For Terry Riley. In that sense, his laptop came closest to what is most commonly conceived of as laptop music: synthesized sound far removed from its raw materials, produced on the fly, generally with rhythmic intent (even when that rhythm slows to the nearly subaural realm referred to as "drone").

Kitundu's use of the laptop was less self-explanatory. The presence of the Apple during his piece, Cerulean Sweet III, was, in fact, a little surprising, given that his compositions center on instruments of his own invention, ingenious hybrids that often involve unfinished wood and old turntable parts. Cerulean is an artfully maudlin piece based on snippets of music by jazz great Charles Mingus, and the audience might have surmised that some of those pre-recorded sounds were emanating from his little computer—and not from the strange contraptions he and Kronos were performing on. In this sense, even if Matmos's use of the laptop best epitomized the aural fact of laptop music, Kitundu's came closer to an audience's experience of laptop music: you had no idea what he doing. Perhaps he was augmenting the sound of his instrument, which he calls a phonoharp. Perhaps he was merely displaying the score. During abstract sound-art shows by laptop musicians, it's not uncommon for someone to ponder whether the performer is just checking his email while the music plays by itself. Such skepticism fades with familiarity, as the rough contours of laptop music become understood and the listener can judge a performance on the basis of the music rather than the player's theatricality. More on that in a moment.

|

First, don't dismiss Fraser simply because of his job designation. It's unlikely Fraser was participating in Kronos's sound as a performer, though since virtually all of the pieces Kronos played that evening involved a pre-recorded portion—like the drum machine beats of Clint Mansell's score for Requiem for a Dream and the old 78-rpm recordings heard in Dan Visconti's Love Bleeds Radiant—it's presumable that he was triggering those. Fraser was primarily, whether with laptop, soundboard, or some combination thereof, shaping the way the music filled the hall. Much contemporary electronica, taking advantage of the tabula rasa of digital sound and the computer's ability to produce immersive multi-speaker environments, is a kind of sound-design as art; Brian Eno's ambient continues to serve as both metaphor and urtext here. These days, musicians including Richard Chartier, Ryoji Ikeda, and Nosei Sakata have made much of little more than a sine wave.

The variously ambiguous roles of those three laptops at that single Kronos event neither bookend the continuum of laptop music, nor even begin to touch on its breadth, but they do signify how differently the machine can be employed in concert.

It would have been one thing for the laptop to simply have come to serve as a digital version of turntables, allowing the user to cue up prerecorded material or to replicate the multi-tracking duties of a recording engineer. But the key to understanding the laptop's role in contemporary music is to appreciate how it took the promise of the studio-as-instrument and turned it inside out. The laptop took the home studio and made it portable, portable in a way that even the four-track tape recorder had only hinted at. A musician seated on stage with a laptop has ability to synthesize and transform sound in a manner that a decade ago would have been unthinkable.

The key word in that last sentence is not "unthinkable" but "manner." Compositional issues as fundamental as matching tempos, or modulating a sequences of notes, or otherwise manipulating self-contained aural elements can be handled, thanks to off-the-rack software, at the level of gesture. Some software, such as Ableton Live, is useable right out of the box; others, such as Max/MSP, provide musicians with a language to learn, but one with which they might craft their own software tools. (Tellingly, many of Max/MSP's engineers are accomplished electronic musicians themselves, including Joshua Kit Clayton, Les Stuck, and Luke DuBois, the latter best known as a member of the Freight Elevator Quartet.) All of which is to say, not only are decisions that once determined how a composer set pen to paper now in the hands of an improviser, so too are the means by which that composer might have honed the sounds in a studio. Many newcomers to electronic music experience an epiphany when they come to understand how inherent improvisation is to composition on a computer.

The laptop is easy to learn and difficult to master. It doesn't take much to figure out how to emit sound, especially if all you want to do is let a series of prerecorded songs overlap ever so slightly to produce a continuous mix; iTunes and other MP3 players have automated that task. Beyond that, though, decisions get murky fast: which software to use, whether to add additional physical inputs, like theremin, external CD players, keyboards, and other such triggers and sound sources. Most of the popular software employed by laptop musicians is available on both Macintosh and Windows platforms, and often Linux as well; musicians, like graphic designers, are attracted to the Apple for its elegant user interface.

Some musicians use the laptop as the equivalent of an effects pedal, just one more tool in their toolbox; for others it is the toolbox itself. At least for beginning laptop musicians, the old koan "less is more" is worth keeping in mind. While the software one employs doesn't directly result in a specific sound, it's safe to say that someone who employs a wide range of equipment and programs is probably going to make more complicated and chaotic music than someone who cuddles up with a single piece of software and tries to make the most of it.

The word "portability" doesn't quite do justice to the laptop's greatest strength. Anyone who has played a double bass has little sympathy for computer-enabled musicians who felt that only with the laptop could they perform regularly in front of live audiences—as if the desktop had been such a hefty or fragile item to lug to a gig. The laptop's true triumph is about a continuity of technological experience. Jimi Hendrix slept with his guitar. Likewise, one laptop is not immediately interchangeable with another. The laptop gets personalized over time—from big things like which programs are loaded, to small things like the user's adjustment to the location of the keys or the idiosyncratic hardware issues that computer manufacturers deny but that anyone who's bonded with their laptop comes to think of as being akin to the machine's personality.

So, what distinguishes a successful laptop performance from an unsuccessful one? Since I'd gladly attend a concert of nothing but old refrigerators, my opinion should probably be taken with a grain of salt, but here goes: Laptop music, whether quiet or noisy, beat-driven or hazy, is generally about process. Most laptop performances consist not of individual pieces but of extended improvisations that run from the beginning to the end of the individual's set. Listening to a laptop musician perform can be less like listening to a composition and more like paying a visit to an artist's studio: The real question is less what went into an individual piece, and more along the lines of what the person has been up to recently, what software they have been mastering, what sonic realms they are exploring.

***

Plastic Devices: Critical laptop innovators and recommended CDs

Any introduction to a specific realm of music necessitates a list of recommended listening. The following are eight individuals, in alphabetical order, who are central to the development of the laptop as a performance and compositional tool, and to its status as a bona fide cultural phenomenon, along with some of their essential recordings. Choosing individuals to best represent such a widespread convergence of technology and culture is a challenge. Come 2006, the laptop is a standard tool, and though innovation continues, the following musicians were actively involved before portable-computing hegemony set in. Also, they all record and tour frequently, which has helped expand their influence and introduce more people to the laptop's potential. So pop one of these CDs into your own laptop's disc drawer and think of it as the 21st-century equivalent of a player-piano roll…

|

Taylor Deupree (b. 1971), based out of New York City, is the proprietor of several record labels, chief among them 12k, whose lo-fi name belies its curatorial focus on high-grade sonic processing, and Term, a trailblazing "netlabel" that offers up for free the occasional recording (often a live performance or a future 12k album-in-progress) to anyone with a good Internet connection and a sizable hard drive. (Visit 12k.com/term.) As a musician, Deupree is an unrepentant minimalist, one who mixes fragility and a mechanistic impulse on albums like stil. (12k, 2002), which revels in its interiority. He frequently collaborates with the musicians who are signed to his labels, notably on Live in Japan, 2004 (12k, 2005) with laptop-enabled guitarist Christopher Willits and Post_Piano (Sub Rosa, 2002) with Kenneth Kirschner, who uses the computer software Flash to compose chance-based works that involve ever-shifting layers of sound files.

|

Fennesz is Vienna-based Christian Fennesz (b. 1962) with laptop and guitar in hand. It's difficult to recall, let alone imagine, there was a moment not so long ago when plugging a guitar into a portable computer would have been a headline-making occasion. But it's true. When Fennesz's Endless Summer (Mego, 2001) was released, the laptop was still considered a self-contained unit, not to mention one still in its infancy. (This is long before Apple's GarageBand software made the connection between laptop and guitar part of its marketing.) Endless Summer caused some minor consternation at the time—the laptop had only in the preceding few years gained enough firepower to serve musicians, and already it was being yanked into the past? And hadn't hip-hop, not to mention rock's own navel-gazing, killed the guitar? Apparently not. Fennesz defied digital purism in favor of music that tasted retro and futuristic; the title isn't the only nod to the Beach Boys, not on an album so expressly languorous, the guitar sometimes plucked for rustic-folk flavor, and at others processed into a hazy background soundscape. Subsequent Fennesz recordings of note include the fractured Live in Japan (Headz, 2003), which requires several close listens for proper orientation, and Venice (Touch, 2004), on which he folds in field recordings, feedback, and David Sylvian's singing.

|

The jaw-droppingly antic collage music of Venezuelan native, and longtime California resident, Kid 606 (given name: Miguel Depredro; b. 1979), brought him quick and widespread attention following the release in 2000 of Down with the Scene (Ipecac), P.S. I Love You (Mille Plateaux), and the uncharacteristically relaxed The Soccergirl EP (Carpark). His nom du laptop, adopted from an old Roland drum machine (the 808 was already spoken for), is perfect for what has come to be known as "laptop punk": a riotous assemblage as alarmingly retrograde as it is almost blissfully cacophonic. That the phrase "laptop punk" went from delightful oxymoron to outright redundancy in half a decade is a testament to the movement's speedy evolution. In addition to the albums mentioned prior, don't miss Kid 606's aptly titled Kill the Sound before the Sound Kills You (Ipecac, 2003).

|

Monolake (b. 1969) personifies the convergence of composition, programming, and performance. It is the pseudonym of Robert Henke, a German craftsman of electronica that at its best burbles with a controlled sublimity—as if the music has been pressed, like autumn leaves, between thick plates of Lucite and then illuminated from below. Monolake was a duo until the other founding member, Gerhard Behles, left the name in Henke's capable hands in order to form a company whose chief product, Ableton Live, is today one of the most popular laptop-performance software titles. Today, one of Ableton's marquee practitioners is none other than Henke/Monolake, each of whose new full-length albums tend to appear in record stores right around the time a new version of Ableton Live is released (it's up to its fifth iteration). Henke isn't merely Ableton's equivalent of a clothes horse; he's also an engineer on the software, bicycling once a week from his home to the company's office to discuss interface design and to report on his latest plug-ins. Each new Monolake album is developed in tandem with the software. Key among them are Cinemascope (ml/i, 2001), road music disguised as sound design, and Hongkong (Chain Reaction, 1997), collecting tracks that laid the groundwork for the digital sedative known as minimal techno. Henke also records under his own name. Robert Henke albums tend to be more spacious, less rhythmic, than the work attributed to Monolake. Check out "Studies for Thunder," the closing track on Henke's Signal to Noise (ml/i, 2004), for its application of minimalist aesthetics to (entirely artificial) environmental atmospherics.

|

Ikue Mori (b. 1953), originally from Japan, came into prominence during the 1970s as a drummer in the New York art-punk band DNA. Since then she has been a fixture on the Manhattan music scene. (She records for John Zorn's label, Tzadik, and the two frequently collaborate.) Mori somewhat famously ditched the drums for a drum machine, eventually developing an intense fixation on the laptop, which she employs for both solo performances and collaborations. Her mild-mannered stage presence masks the fluidity and speed of her music, which is marked by simultaneous layers and samples of traditional instrumentation. She is an equal partner in the trio Mephista with pianist Sylvie Courvoisier and drummer Susie Ibarra. Recommended are Mori's recent solo album, Myrninerest (Tzadik, 2005), which has a certain mystic whimsy, and Mephista's Black Narcissus (Tzadik, 2002); by positioning her laptop between piano and drums, Narcissus highlights the controlled serendipity she brings to the mix. Also worth tracking down: The Turntable Sessions: 2001-2002 Volume 1, a project initiated by Billy Martin, drummer with the jazz act Medeski Martin & Wood; the album teams her live with echo-laden DJ Olive on three tracks, one a trio with Martin.

|

The work of British musician Scanner (a.k.a. Robin Rimbaud, b. 1964) posits the laptop as a passport that allows him to move easily between cultural worlds. One evening he may perform a set live at a club, using the instrument from which he took his name to rip unprotected speech from the airwaves, his laptop emanating an improvised emotional soundtrack that lends context and drama. The next he may be at a museum, performing one of his pieces that serve as both art and commentary, like 52 Spaces (Bette, 2002), an audio-visual reduction of Michelangelo Antonioni's film The Eclipse, or the knowingly titled Warhol's Surface (Intermedium, 2003), which applies his Scanner MO to recordings of Andy Warhol. Rimbaud is increasingly involved in collaborative, event- and site-specific work, like summoning voices of the past in an installation at a 13th-century hospital, or composing for ballet, or doing sound design for a horror movie. It's the laptop that allows someone so mobile (not just geographically but artistically) to keep familiar tools at hand.

|

Los Angeles native Carl Stone (b. 1953), who studied with composers Morton Subotnick and James Tenney, splits his time between Japan and America. Stone's music often involves field recordings from his travels, though those sounds might be so contorted, into percussive noise or an ether silence, that they're nearly unrecognizable. There's something about his reputation as a peripatetic individual that makes his laptop seem to double as a suitcase, and his performances feel like montage aural slide shows of his latest activities. His frequent residence in Japan has brought him into the circle of indigenous microsonic noise labeled as "onkyo"—represented by musicians such as Testu Inoue, Sachiko M, and Nobukazu Takemura—which is often, though not exclusively, produced on laptops. Stone has a particular interest in immersive installations, and I've witnessed him wow both an unschooled audience in New Orleans and a room of his peers in San Francisco with his surround-sound control of space and time. His Nak Won (Sonore, 2003) shows his mastery of choppy momentum, dozens of samples falling down a staircase in resplendent chaos. And even better is pict.soul (Cycling '74, 2002), a collaboration with the ultra-rarified Inoue, during which they riff with sonic particulates that make most minimalism sound like Wagner by comparison. (And lest this music be mistaken as a youth movement, note that a laptop-wielding Subotnick, born two decades prior to Stone, was a highlight of the 2005 San Francisco Electronic Music Festival, at which he collaborated with Miguel Frasconi.)

|

Keith Fullerton Whitman (b. 1973), who grew up in New Jersery and today resides in Boston, maintains a second existence under the name Hrvatski, but even dual identities aren't enough to encompass the breadth of his musical activities. As Hrvatski he has perpetrated some of the most blindingly ecstatic anti-dance music imaginable, beats that shred themselves as they go. Witness the often brazen wildness of Swarm & Dither (Planet Mu, 2002). But in time, he's emerged from that moniker's shadow as a thoughtful, knowledgeable musician for whom the laptop is both a room in which he can seclude himself as well as just another piece of equipment in his shed. His best work involves guitar and laptop, notably the lush soundscapes of Playthroughs (Kranky, 2002) which update the live looping pioneered by guitarist Robert Fripp in the 1970s. Whitman has an ongoing partnership with Greg Davis, and the two released a maddeningly expansive compilation of live recordings last year, Yearlong (Carpark). By the way, though Whitman jokes that his home studio does double duty as his bedroom, he isn't married to his laptop. The album Multiples (Kranky, 2005) put him to work on vintage equipment housed at Harvard and MIT, including the Serge Modular Synthesizer Yamaha Disklavier.

***

The Incredible Shrinking Computer: Music in the palm of your hand

The riddle goes: What part of your body disappears when you stand up? The answer: Your lap. To rephrase the question: What happens when your laptop disappears? That is: What happens as you get more accustomed to mobile computing and your threshold for acceptable portability becomes even more demanding—and those demands are met? The foreseeable answer is music in the palm of your hand.

|

Despite all the activity in laptop music today, it seems unlikely that the laptop will, as a self-contained unit, have the sort of lifespan enjoyed by the piano, the string quartet, or the ukulele. There is no reason to suspect that the laptop is anything more than a transition object, as the computer slowly finagles its way into everyday life. The rise of the laptop has to do not with technology having reached a point where portability made pre-existing computer music feasible for live performance; it's that the technology reached a point where the portability led to more rapid adoption, which at a certain critical mass led to unexpected consequences, like laptop battles, as organized at laptopbattle.org, in which individuals vie for the reaction of judges and audience; gestural interfaces, like the optical sensors added to CD players; homebrew electro-acoustic experimentation, and so forth.

The watchword for this sort of down-the-road activity is "pervasive" computing. Prognostication aside, it might be helpful, in closing, to just run through a variety of currently existing small electronic devices, some of them laptop-enabled, many if not all of them the spawn (or kissing cousins) of laptop music:

For the most part, this essay has been concerned with the realm of art, but it's worth noting that the biggest selling category in computer-based music is ring tones for cellular phones. These began as single-line melodic reductions of songs, from Vivaldi to 50 Cent, but as cell phones' specs have improved, so too has the accompanying music, much to the annoyance of moviegoers and teachers. Today, phones feature multiple voices, richer sound, and the ability of phone owners to shape sounds themselves. Some phones include tools for composing. Much as you can take a photo with your in-phone camera and email it to a friend, so too can you make a little tune and send it out into the world.

In this context, the first truly portable computing device of any practical consequence (attention aficionados of Apple's Newton: this means factoring in market penetration) was, arguably, the Palm Pilot, later re-christened simply the Palm. Microsoft developed a competing operating system, the Pocket PC, which features a slimmed down edition of its flagship operating system, Windows. Both Palms and Pocket PCs have music tools available, from simple metronomes and guitar tuners to mini-keyboards, samplers, and multi-track recorders. For some examples of this sub-laptop music, check out the community that's former around Bhajis Loops (chocopoolp.com), a music program for the Palm whose users include electronic minimalist Richard Devine.

It's been noted that the laptop is significantly more than a digital turntable, but that isn't to say that the laptop doesn't serve frequently as little more than an MP3 player that can crossfade between tracks. A recent system called Final Scratch has eked out a common ground between computer and vinyl LP by providing DJs with a hybrid that allows them to use the LP as the interface for manipulating music, even though the music itself is stored not on the surface of the album but in a computer that is hooked up to the turntable. Despite digital reticence on the part of vinyl DJs, the equipment has caught on, in part due to the creative involvement of Richie Hawtin (a.k.a. Plastikman) and John Acquaviva. (There's a similar system named Serato, manufactured by Rane.)

Many of today's electronic musicians developed a fondness for lo-fi, synthetic sound while playing video games in their youth. While the soundtrack to the average video game has matured considerably, musicians' tastes haven't necessarily. Not only do communities exist for the production at the 8- and 16-bit levels of games of yore, many musicians also produce music on everything ranging from old Atari units to today's Game Boys. Perhaps in response to this trend, a recent Nintendo DS cartridge, Electroplankton, is a sort of audio game or sound toy. It has no endgame, no specific goal, except making noise with an interactive psychedelic interface. Electroplankton takes advantage of the DS's dual screens, one of which is touch-sensitive.

Speaking of alternate interfaces, the Tablet PC, on which the entire screen is touch-sensitive, shows a lot of promise for innovation. It's a standard feature on many Windows laptops, and the company is pushing a new "ultra mobile" protocol that may dispense with the keyboard entirely. Then again, as the iPod's success has shown, it's likely that such hands-on computing won't reach mass popularity until Apple joins the party.

Though circuit-bending predates the laptop, its popularity has surged of late, as electronic musicians have sought out new sources of sound. Circuit-benders take pre-existing hardware—most famously gadgets like Speak & Spells and other children's toys—and mess with the innards until they squeal to the owner's satisfaction and, more to the point, surprise. The founder of circuit bending is Reed Ghazala, who compiled his decades of experimentation last year in the book Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments. I recently moderated a panel discussion at the first annual Maker Faire, held by Make magazine, in which I brought together three musicians who make their own instruments: a pair of these circuit-benders, Chachi Jones (a.k.a. Donald Bell) and univac (a.k.a. Tom Koch), plus Krys Bobrowski, whose inventions include a giant glass 'armonica and horns made of dried kelp. To hear those three tell it, the definition of an instrument is as much in play at the dawn of the 21st century as the concept of the composition was toward the end of the 20th. They, along with Kitundu and folks like Pierre Bastien (who has built his own automaton orchestra), Matt Heckert (of Survival Research Labs), Ken Butler (whose guitars are known to sprout from tennis rackets), and Monolake (who has developed the "Monodeck," a personalized bit of hardware that serves as a central hub for his software and equipment) are at the forefront of where instrumentation is headed.

Also at the Maker Faire this year was the crew that developed the Monome, a USB-enabled grid that serves as a sample trigger for laptops, though that description doesn't do it justice. The promise of that particular device, which retails for $500, isn't just its simplicity or the open-source community of musician-developers who will share the code they program to make the most of the new instrument. The promise is the idea that the mass production of such physical devices is no longer only in the hands of big companies like Yamaha and Korg.

But for all the various small-scale devices being produced today that make music, none has the open-ended potential of the laptop. Laptop musicians aren't just collectively working to create a shared understanding of how the device functions as an instrument, they are also individually, as they piece together the perfect balance of software and hardware, making singular instruments that are all their own.

***

Marc Weidenbaum was an editor at Pulse! and a co-founding editor at Classical Pulse!, and he consulted on the launch of Andante.com. Among the publications for which he has written are Down Beat, e/i, Jazziz, Stereophile, Salon.com, Amazon.com, Classicstoday.com, Big, Make, and The Ukulele Occasional. Comics he edited have appeared in various books, including Justin Green's Musical Legends (Last Gasp) and Adrian Tomine's Scrapbook (Drawn & Quarterly). He has self-published Disquiet.com, a website about ambient/electronic music, since 1996; it features interviews with, among others, Aphex Twin, Autechre, Gavin Bryars, Pauline Oliveros, and Steve Reich.