Anyuak People Of South Sudan

"A Brief Moment with the King, Adongo Agada Akway Cham"

By Elly Wamari

ewamari@nation.co.ke

September 21, 2006

A day with the kings of Sudan

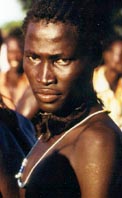

With a cigarette between two long fingers that maintain closeness to his dark lips, and an indifferent expression on his face, Adongo Agada Akawi Cham’s posture by the poolside tables of Boulevard Hotel in Nairobi present him as an ordinary guest. The three women conversing at a table nearby would probably consider it a joke if they were to be let into the fact that the lone man tensely puffing away cigarette smoke in their vicinity was a royalty.

|

|

Who would blame them? Adongo comes across as a very ordinary person. Not even the three-piece suit he has on would betray his position. The suit is an everyday cut.

But he is King of the Anyuak people of South Sudan. There, he is fully addressed as King Adongo Agada Akwai Cham. He would hardly pass unnoticed in Anyuak country, unlike at Boulevard hotel.

Ideally, his territory spreads into Ethiopia. One thing worries him lately, which explains his rather distant look. His tribesmen who got cut off to the Ethiopian side when the colonial borders were defined, are in trouble.

He now has to worry about the thousands of "displaced people", who recently crossed over to the Sudan side after an armed invasion by an Ethiopian ethnic community they refer to as "highlanders".

Those are matters of his territory, colonial borders notwithstanding. Concerns of the Anyuak people, whether on the Sudan or Ethiopian side, lie within his responsibility as king.

To demonstrate how seriously he holds the matter, he made these worries a point of discussion on August 16 at a diplomat’s home in Nairobi, where he and 13 other Kings, Chiefs and Emirs from South Sudan had a reception as they passed through Kenya on route to a tour of South Africa, Botswana and Ghana.

Inspired by a return to peace in their land, traditional leaders of South Sudan are now consolidating their hitherto disrupted positions. The tour to the three African countries deliberately selected was aimed at studying other traditional royalties and their relations with central governments. And so, as he sits pensively by the Boulevard hotel poolside, King Adongo has just returned from the tour. He gathers his thoughts during a break from a debriefing session they are holding at the hotel in transit to their respective kingdoms and chieftains.

The date is September 3, when he relents to sharing his life as a South Sudanese traditional royalty. As typical of traditional leaders, he has five wives, and tracks of land and cattle as his property. One of his wives just gave birth to his 13th child as he was on the tour. "The Anyuak people have had kingship for centuries," he begins. That opening line betrays his fluency with English.

Several of his fellow traditional leaders are struggling with the language, the other reason he stands out tall among them, apart from his dress code and height.

There’s a little background to that. Before being named king upon his father’s death in 2000, Adongo, now either 47 or 52 (he talks of conflicting information about his date of birth), was living ordinarily in Canada with his family. The war that broke in his country in 1983 had driven him out. He went to Syria, then Cuba, and finally to Canada, where he had considered settling in. Not being the first son, he had at no moment expected to become King. Surprised he was, therefore, when it turned out that it was he whom his father had secretly named the would-be heir of the throne. Ordinarily, his elder brother would have been the choice.

The appointment fell flat on his laps unexpectedly. Suddenly, he was caught between a tough choice — to decline the appointment and continue living in a foreign country, or accept and go back home. "That was a difficult moment for me. Anyway, I finally decided to return to my country. I was then crowned King in 2001."

King Adongo’s authority in Anyuak country can be assessed through the responsibility that comes with his position. He holds the last word on community governance matters, including resolving internecine as well as externally instigated communal disputes. The fact that his traditional territory spreads into Ethiopia complicates things further. He has to obviously consider foreign relations at that level.

The return of peace to the larger country has reawakened interest in the traditional systems that, though were not extinguished during the war, had, in King Adongo’s perception, been threatened. The absence of a unifying body of all traditional leaders to consolidate their interests and relate these with the central government for effective governance to community level, has been an issue of discussion. Traditional leaders want that badly, and so one of King Adongo's latest engagements is to participate in its formation.

It was such interest that sparked the three-nation African tour. South Africa, Botswana and Ghana are examples of countries in which strong traditional governance systems co-exist with the central governments, hence their selection as destinations for the tour.

That trip has now lit up a fire in the various other kings, paramount chiefs, and princes who took part. They now want to establish an association to collectively serve the interests of their respective communities.

In that way, they will have a unifying voice, and perhaps find strength to play a part in resolving the Darfur crisis, for example. And talking of the troubled Darfur region, King Adongo expresses his opinion. "Darfur is considered to be in Northern Sudan. We are in South Sudan, but what is going on there saddens us as southerners. We want peace in that part of Sudan." A conversation thereafter with Paramount Chief Dennis Dar Amallo Kundi, of the Bari people in Juba, yields similar discussion lines. But he keeps emphasizing the need for a "rest house" for all chiefs of Juba, where the "high council of chiefs" in the region could also hold decision-making meetings.

A hearty chat with him ends my brief encounter with a section of Sudanese traditional aristocracy. Their humility, however, leave me a little surprised. They are different from the more familiar big-time royalty that comes with significant amounts of sophistication.

The people call themselves Anywaa; others particularly their neighbors [Nuer,

Dinka and Shilluk] simply know them as Anyuak.

The Anywaa society is communal. It is obligatory to share resources and assist one another in times of famine and disease. The Anyuak engage in collective construction and building of the King''s royal palaces; the cultivation and weeding of his fields and gardens.

The Nyie obligates for these services by providing drink and food for which the people feast, dance and sing for several days in his home. Other social activities include hunting and fishing. However, the acquisition of fire arms has made hunting a solitary affair.

The Anywaa have no ceremonies attached either to birth, graduation into adulthood; nyako for girl and wadmara for the boy [ready to marry] or marriage. The only custom linked to marriage is the payment of demuy [beads] and a few heads of cattle as dowry.

The bride stays in her parents’ home until the dowry or half of it has been paid, after which she moves to her husband. Sometimes a poor groom may raise up to two children with his wife while she is still staying with her parents.

The Nyie gives his daughters to wealthy grooms. Indeed, flirting with the Nyie’s daughter could invoke his wrath resulting in confiscation of one’s wealth or abduction of three girls from one’s village. Several [sometimes up to ten] Anyuak marriages could be broken by breaking one marriage in the line. The demuy have become rare, so they are circulated and hence could even come back to the original owner in the course of several marriages.

The Nyie does not die but returns to the river. When he discovers that he can no longer hold on, he announces to his court that he has already returned to the river so his anointed son remains with the people.The new Nyie is placed on the Ocwak [royal throne and bead].

The deceased Nyie is buried in an ordinary way, since his

spirit is assumed to have returned to where he came from.

People don’t cry, they instead beat the royal drums and blow the trumpets

singing song of praise to the departed Nyie. Sometimes, a person would mention

in praise of the Nyie all the materials things he received from him.

The Anyuak kingdom used to be a

federation of villages headed by an independent Nyie. These villages were

constantly feuding among themselves for the control of the Ocwak – the royal

throne and bead.

This state of insecurity prompted the British colonial administration to make

Nyie Agada Akway king of kings ostensibly after the Ethiopian feudal system

[Emperor Haile Sellasie, was king of Kings] rendering the Ocwak to permanently

remain in his possession and protection [Adongo area has a huge army to protect

the Ocwak].

All other Nyie come to his court to be put on Ocwak temporarily, for a few days

depending on how much he trusted him, after the payment of three demuy. The Nyie

has several kway luak or sub-chiefs who administer smaller villages.

The Anyuak are strongly religious

and have strong beliefs in spirits to which one returns when one dies. One could

communicate with the departed through a medium or when one becomes possessed by

the spirit.

The Anyuak attach important to "cien" or curse and "gieth" or blessing and the

two create order in Anyuak society. For instance, before a man dies, he confides

his will to somebody, who declares himself as the trustee of the will once the

death is announced. Tradition has it that nobody can change or disobey the will

of dead person.

Marriage is expected of every adolescent. He pays bride price in demuy, cattle and sometimes money. The tradition of money started with the Ethiopian Anyuak and has now become common due to the scarcity of the demuy.

Marriage to blood relatives and

incest is abhorred such that the social stigma can force one to find ease by

going to live in a far off place. The Anyuak have an attitude of keeping pure by

not marrying from certain ethnic communities neighbouring them.

Naming: The Anyuak have typical first [Omot/Amot], second [Ojullo/Ajullo], third

[Obang/Abang] and twin [Opieu/Apieu; Ochan/Achan; Okello/Akello] births with ‘O’

and ‘A’ connoting male and female respectively.

A child left in the womb by the death of the father is named Agwa; and Ochalla/Achalla stand for the child born for a dead brother. Beside these names, the Anyuak have many different and occasional names including names of the important personalities in the clan or communities as a whole.

Anyuak literature is orally expressed in form of poems, songs, folktales, riddles and stories. These are handed over from generation to generation. The main music instruments included: thom [guitar], bul [large drum], tung [horn of kudu fitted with awal [guard], odolla [small drum].

The Anyuak like other Nilotes have pany [hold in the ground for founding sorghum], lek [pole for founding] and lul [for winnowing of sorghum.] The Anyuak wear lots of beads and other artifacts like the tail of giraffe.

The Ajiebo [Murle], Nuar [Nuer],

Dhuok [Suri], Galla [Oromo] and others neighbor the Anyuak. Their relations are

far from cordial particularly with the Nuar who have perpetually pushed them to

the east.

The Anyuak used to engage in slave raids on their neighbors. They sold their

slaves to the Highlanders for firearms. This must have been the source of

conflict between Nyie Akway Cham and the British colonial authorities in 1912.

Nyie Adongo Agada was enthroned in 2001. In May 2003, a peace agreement between the Anyuak and the Murle was sealed in Otallo under the auspice of Nyie Adongo. This has stabilized the relationship with the Murle. The conflict in Gambella between the Anyuak and Ethiopian Highlanders is affecting the Anyuak in Pochalla and Akobo.

The war in Sudan and the demise of Mengistu in 1991 have pushed many Anyuak to seek resettlement in America, Europe and Australia. There is a large Anyuak Diaspora in Canada and USA.

Anyuak Mini Museum

Below images are the recovered material and visual cultures of the Anyuak. Most of material and visual cultures were collected by Evans-Pritchard during his period of fieldwork amongst the Anyuak between early March and May 1935 (E.E. Evans-Pritchard, 1940, The Political System of the Anuak of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, p. 3).

Documentary

THE MAN WHO BECAME KING (Clip)

Edith Champagne

Don Murray (writer)

1 August 2007 (USA)

Documentary

In 2000, the King of Anyuak dies, naming one of his sons, Adongo Agada, as his successor. Anyuak is in the Sudan, with 70,000 people; civil war has raged for more than 20 years. Adongo is reluctant: he is newly in Canada, working and trying to bring his wife and eight children to join him. He returns to the Sudan, under armed guard. We see his coronation. He's a Christian conflicted by tribal beliefs in polygamy. He wants to modernize his people, build a school, and improve farming in the face of tradition. In an impoverished, war-weary land, can he leverage power? He also needs to take care of his family. Can he find a path to be both a wise leader and a responsible father? Is it good to be king?

USA:75 min | Canada:75 min

Nomad Films